History is fascinating, but frustrating

wnowak10

I came across the following post, recently:

In short, Mortimer makes a fascinating argument that the development and proliferation of mirrors contributed to a shift in public self-awareness. Being able to clearly and frequently see their self-image, citizens grew more consumed by self and became less communally-attached. It is a pretty cool argument, and Mortimer writes in a more compelling prose than I ever could.

But my interest in data science has always made me grow frustrated with historians. Where is the data? The proof?

He gives data on mirror prices, and says that mirrors “led to a huge rise in the number of portraits commissioned, especially in the Low Countries and Italy,” though no citation is given. Even if we accept that mirrors are more prevalent (I definitely buy that)…how can we trust his assertion that “The very act of a person seeing himself in a mirror or being represented in a portrait as the center of attention encouraged him to think of himself in a different way.” Historians do this too often, I find. It’s a fun and compelling story, but the author provides little in the way of objective proof. The arguments he presents (the deterrence of banishment, changes in chapel construction, letter writing) make sense, but the lack of empirical evidence weakens them. I find it unlikely that I could not theorize differently, and propose reasonable support for my own idea.

Perhaps, in seeing oneself in a mirror and realizing the vast difference between one’s unflattering visage and the common image of God, individuals increasingly shirked their conception as singular selves, seeking refuge as a commoner under God. Their refutation of self drove the peoples of the middle ages towards increased economic inter-dependence and increased migration, both indicative of a broadening faith in the community instead of individual selves.

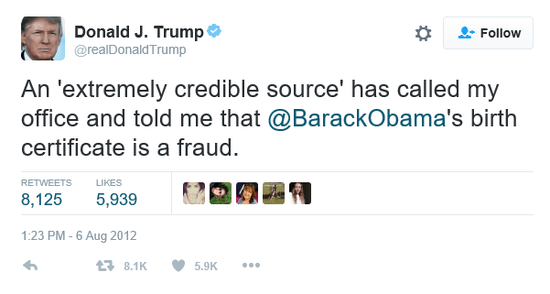

Admittedly, my argument is pretty weak, but I am not a New Yorker writer. Historians need to hold themselves to higher standards. If our most revered historians can make unfounded claims in advancing a compelling narrative, why should expect others (see: politicians to be different?